Transcript:

A. Introduction

In German criminal law, four requirements have to be satisfied before someone may be punished for a crime:

1) The elements of a certain criminal offence must be fulfilled;

2) the deed must be illegal, i.e. there must be no justificatory defence;

3) the defendant must be guilty, i.e. responsible and acting without exculpatory defences;

4) there must not be any other exemptions from punishment.

The elements of punishability are subject to art. 103(2) of the German constitution: “An act may be punished only if it was defined by a law as a criminal offence before the act was committed.” This is one of the most fundamental rules of German criminal law.

The principle of legality is also known in Latin as nulla poena sine lege. It applies most prominently to the individual offences themselves. However, it also requires e.g. that defences defined by statute are not curbed beyond the letter of the law.

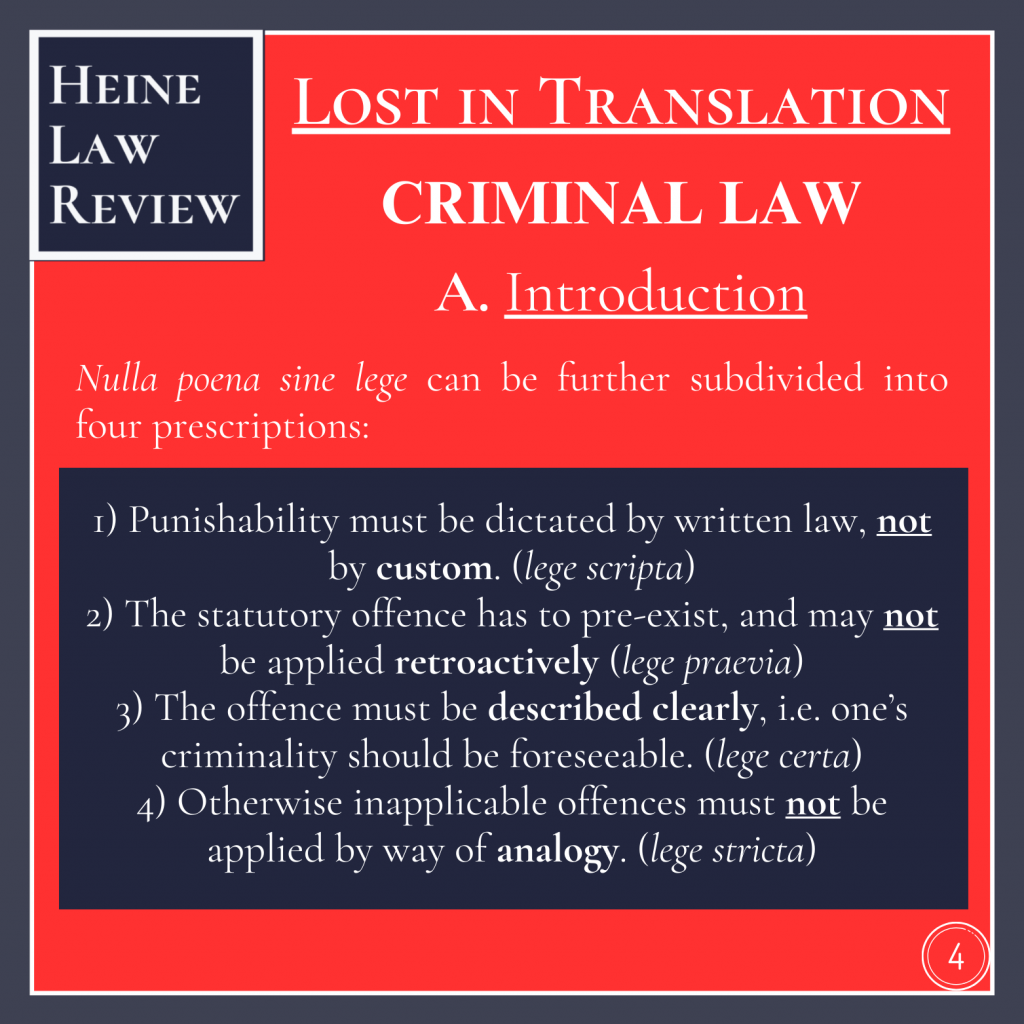

Nulla poena sine lege can be further subdivided into four prescriptions:

1) Punishability must be dictated by written law, not by custom. (lege scripta)

2) The statutory offence has to pre-exist, and may not be applied retroactively (lege praevia)

3) The offence must be described clearly, i.e. one’s criminality should be foreseeable. (lege certa)

4) Otherwise inapplicable offences must not be applied by way of analogy. (lege stricta)

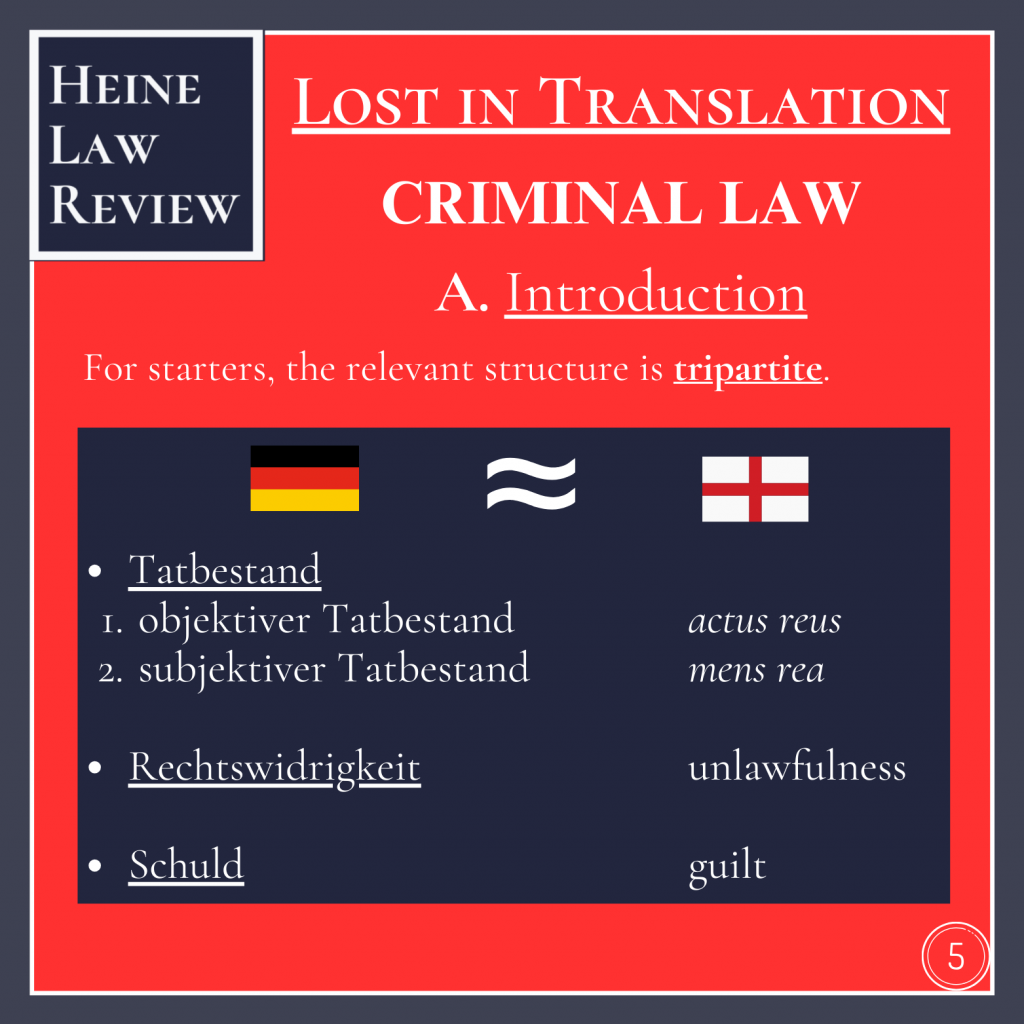

For starters, the relevant structure is tripartite.

I. Tatbestand

- objektiver Tatbestand (actus reus)

- subjektiver Tatbestand (mens rea)

II. Rechtswidrigkeit (unlawfulness)

III. Schuld (guilt).

B. Tatbestand

The Tatbestand is the positive description of the individual offence. This may include both the objective actus reus and the subjective mens rea.

For example, theft is defined by s. 242 as taking moveable property belonging to another away from another party (objektiver Tatbestand), with the intent of appropriating it for themselves or a third party (subjektiver Tatbestand).

If the mens rea is not specially defined, s. 15 implies that the offence must have been committed with intent. The offender must at least be aware of and condone the objective elements being fulfilled, even if they do not aim for it or take it as a certainty (conditional intent).

The offence may be committed by mere negligence only if this is expressly provided for. Hence, e.g. s. 212 deals with (intentional) homicide and s. 222 separately with negligent homicide.

Individual offences can be broadly divided into conduct-based offences (Tätigkeitsdelikte) and result-based offences (Erfolgsdelikte). The result in question may be an actual success (e.g. someone’s injury or death) or the concrete threat of such. There are also result-based offences which are nevertheless conduct-bound, such as driving a vehicle and causing danger to persons or property (s. 315c).

To illustrate this, shooting a gun may be a crime unto itself under weapons legislation, whereas committing a homicide by these means firstly requires causality. If the death of the victim could reasonably have happened without the shot being fired, the shooter is not responsible (necessary condition or conditio sine qua non).