Transcript

A. In contract law

Drunkenness, or intoxication and addiction in general, may constitute pathological mental disturbances, preventing the free exercise of will.

Addiction as a permanent state of mind leads to complete incapacity to contract acc. to s. 104 nr. 2 of the Civil Code (BGB). However, this may be limited to the purchase of substances or to financial decisions.

Mere intoxication as a temporary mental disturbance, on the other hand, does not take away the affected person’s capacity. Still, s. 105(2) BGB renders their declarations of intent void. This leaves their ability to receive others’ declarations of intent untouched.

Needless to say, the same applies to full-on unconsciousness.

B. In criminal law

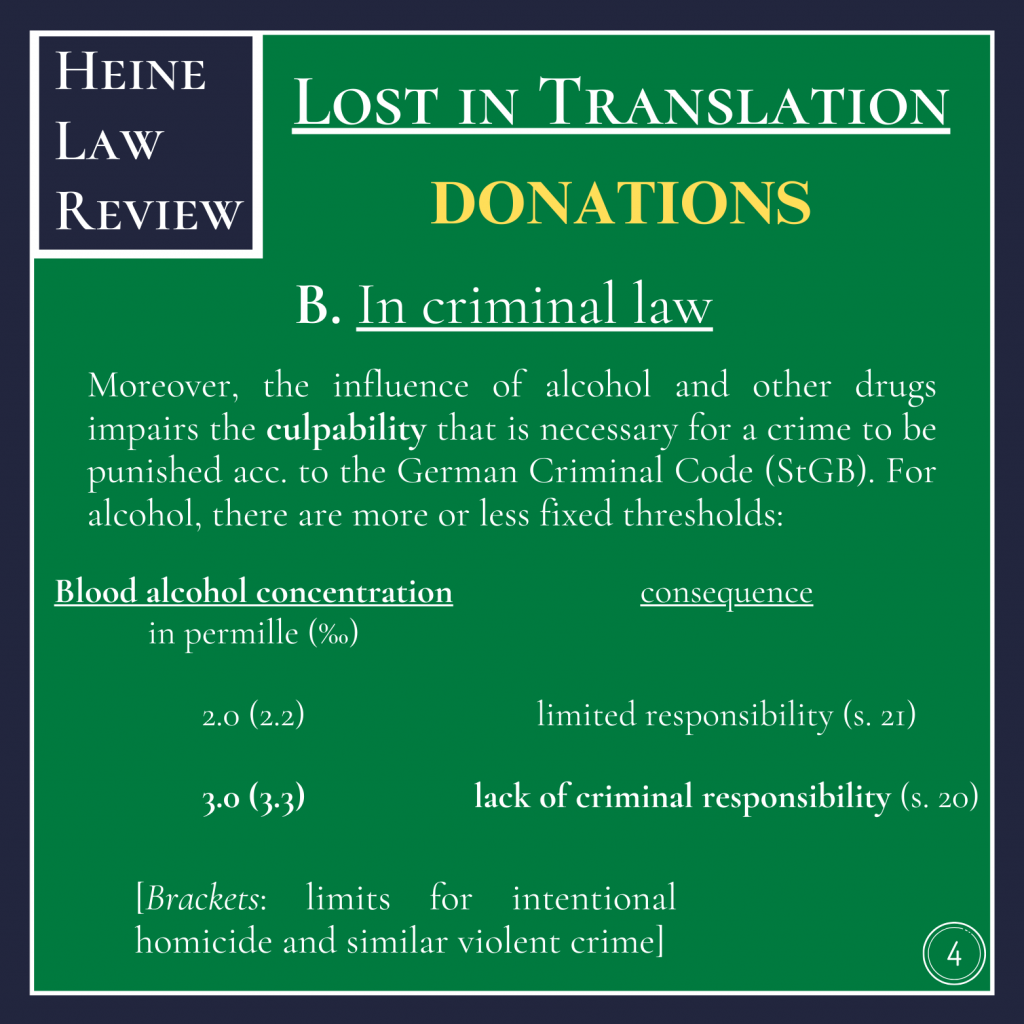

Moreover, the influence of alcohol and other drugs impairs the culpability that is necessary for a crime to be punished acc. to the German Criminal Code (StGB). For alcohol, there are more or less fixed thresholds:

Blood alcohol concentration in permille (‰) / legal consequence

2.0 (2.2): limited responsibility (s. 21)

3.0 (3.3): lack of criminal responsibility (s. 20)

[Brackets: limits for intentional homicide and similar violent crime]

Jurisprudence also affirms the perpetrator’s punishability for their culpability in causing the unfree state of mind (actio libera in causa). This is not considered an exception to the principle of simultaneity (Koinzidenzprinzip) but rather justified by the idea that the perpetrator has intentionally or negligently caused both his state and the subsequent offence. However, this applies only to result-based offences (Erfolgsdelikte), not conduct-based offences such as drunk driving.

S. 316 punishes driving under the influence.

S. 315c StGB treats DUIs related to motorized vehicles as an endangerment of road traffic if the life or limb or property of significant value of another person are thereby (concretely) threatened.

S. 323a criminalizes all intoxication if the person concerned goes unpunished for another offence, with the sentence not exceeding that of the other offence.

Driving a car upwards of 0.5 ‰ qualifies as an administrative offence. Punishability requires a condition of unfitness to drive safely. For motorized vehicles, this is assumed if the BAC exceeds either 1.1‰ (absolute unfitness) or exceeds 0.3‰ with the driver exhibiting any outward signs of unfitness, such as zigzagging (relative unfitness). The limits for bicycles are 1.1‰ and 0.3‰, respectively.